Gene editing for cell therapies and, in particular, for iPSC-derived cell therapies have acquired additional interest recently as therapeutic developers are seeking technologies to create cell therapy products that are engineered to: 1) target the disease biology; 2) avoid unwanted immune reactions; and 3) make those cell therapy products more effective in targeting the disease.

For the IP strategy, there are two main elements to consider in respect to any technology:

- How do you make sure you do not infringe or potentially infringe on a third-party IP (patents and Freedom to Operate or FTO) in respect any of those technologies?

- How do you protect your own innovation to ensure your innovative therapeutic product is protected from being copied?

There are two main aspects that influence IP strategies here: what genes or chromosomal elements are to be modified (i.e., deleted or inserted) and what tools (gene- editing technologies) are deployed to generate safe and targeted cell therapies.

Gene-editing technologies have been around for a while. Many of the earlier technologies, such as transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) and Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), have been well tested and are well-established technologies. The patent landscape around those is pretty clear with only some patent rights remaining. One big disadvantage of those established technologies is the time required to generate the components needed for gene editing.

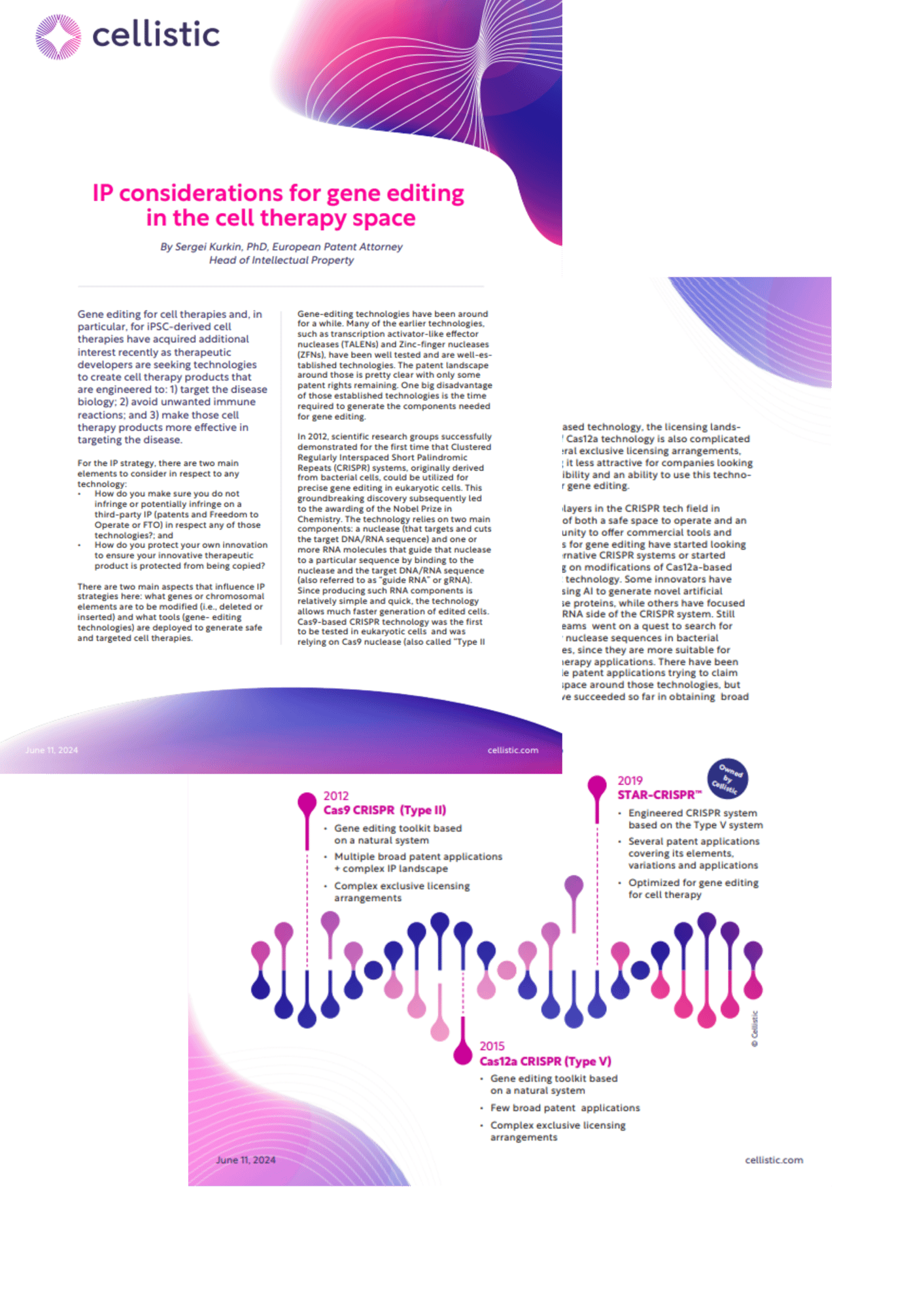

In 2012, scientific research groups successfully demonstrated for the first time that Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) systems, originally derived from bacterial cells, could be utilized for precise gene editing in eukaryotic cells. This groundbreaking discovery subsequently led to the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The technology relies on two main components: a nuclease (that targets and cuts the target DNA/RNA sequence) and one or more RNA molecules that guide that nuclease to a particular sequence by binding to the nuclease and the target DNA/RNA sequence (also referred to as “guide RNA” or gRNA). Since producing such RNA components is relatively simple and quick, the technology allows much faster generation of edited cells. Cas9-based CRISPR technology was the first to be tested in eukaryotic cells and was relying on Cas9 nuclease (also called “Type II nuclease”). This discovery led to subsequent multiple broad patent applications and serious legal disputes over the ownership of that technology. While Cas9-based CRISPR technology is well-established by now, several complex exclusive licensing arrangements for that technology made it more difficult for many companies to rely on it for their product development.

Cas12a technology (or also called “Type V-A”) was subsequently discovered, differentiating itself from Cas9-based systems by only requiring one shorter RNA molecule (with the Cas9 system, two RNA molecules were fused by the scientists to create one). That discovery then led to a couple of broad patent applications around Cas12a-based systems. As the Cas9-based system and its variants were already subject to different patent applications by the time Cas12a system was identified and tested, the IP landscape of that type of CRISPR system is less crowded and only dominated by a couple of broad patents. As is the case for Cas9-based technology, the licensing landscape of Cas12a technology is also complicated by several exclusive licensing arrangements, making it less attractive for companies looking for flexibility and an ability to use this technology for gene editing.

Many players in the CRISPR tech field in search of both a safe space to operate and an opportunity to offer commercial tools and services for gene editing have started looking for alternative CRISPR systems or started working on modifications of Cas12a-based CRISPR technology. Some innovators have been using AI to generate novel artificial nuclease proteins, while others have focused on the RNA side of the CRISPR system. Still other teams went on a quest to search for shorter nuclease sequences in bacterial genomes, since they are more suitable for gene therapy applications. There have been multiple patent applications trying to claim broad space around those technologies, but few have succeeded so far in obtaining broad claims.

One example of an engineered Type V system is STAR-CRISPR™ technology (recently acquired by Cellistic), which is based on Type V systems but leverages an engineered split gRNA design. Such a system was further optimized for gene editing for cell therapy, and many RNA molecules have been tested before an optimized system has been generated for specific target genes. STAR-CRISPR™ not only differs from the systems that previously claimed naturally-derived Type V systems, but it has also been further fine-tuned for specific applications for deletion and insertion of genetic sequences. The system has been subject to multiple patent applications covering its elements and variations, as well as its applications for deleting and inserting specific sequences into specific chromosomal locations.

While the CRISPR gene-editing toolbox is one important element of successful fast generation of targeted cell therapies, the second important component for IP considerations is what target genomic elements should be edited. There are two primary types of edits: gene deletions (by either deleting a portion of the gene or the whole gene) and insertions of specific sequences into specific chromosomal locations.

One of the requirements for having a successful specific gene sequence edited is that the CRISPR system (i.e., the nuclease and the RNA) must target a very specific genetic sequence without touching any other sequence in the genome (to avoid so called “off-target effects”). Many patent applications have been filed around different types of technologies avoiding off-target effects. In addition, in the age of AI technology, many players realized that having a good data set of what target sequences work better for a particular goal could provide a competitive advantage. While many online tools are available, specificity of each CRISPR system and each target genomic sequence make such experimental data invaluable to develop superior AI/ML-based algorithms that allow selecting the best target sequences. Those AI/ML approaches have also been protected using patents and trade secrets as most of the specific AI models are kept in-house.

While gene deletion has been fairly well-tested, inserting a particular sequence has been more challenging using CRISPR technology. There have been attempts to improve this process using different technologies, and many innovators filed patent applications around their improvements.

Another set of gene edits being intensively explored today focus on avoiding immune responses caused by the introduction of edited cells into the body. While some basic technology around immune-evasion has been described more than 20 years ago but no standard has emerged yet, many market players are attempting to develop their own allogeneic edits by trying to identify a unique combination of genetic inserts and deletions that provide the best efficiency and safety for such therapies. Many of those ideas have originated from – and been patented by – academic institutions, and have been licensed by biotechnology companies to further develop and introduce into their target products.

Having to monitor this space to ensure FTO while filing patent applications to protect your own advances is essential to ensure the end therapeutic product has strong IP protection. As the development of such allogeneic cells takes time, , a stepwise approach to protecting innovation as the improvements are identified is commonly applied. Often, when additional edits, specific sequences or modifications to those sequences are identified, a new patent application is filed to make sure such an improvement is protected. In some cases, applicants may decide to abandon their “older” patent filings that no longer cover the technology they pursue. However, many maintain their multiple patent filings, both: (a) to ensure they have FTO with respect to the broader technology area; and (b) to prevent others from claiming the space that could be potentially interesting for prospective partners or investors. Therefore, monitoring of key players in the field and the life of a patent application is an important element of an IP strategy when dealing with this technology.

It is important to have the right IP strategy with respect to monitoring IP landscape and protecting your own innovation. The specifics of such a strategy would depend on the business model and the specific technologies your team considers using for generating a therapeutic product. Finding a good balance between navigating existing IP rights and filing your own patent applications for your gene-edited therapies is essential for ensuring exclusivity is maintained as you continue to develop innovative cell therapies.

Author: Sergei Kurkin, PhD, EPA